Redefining Immunity: How the CDC Changed the Definition of a Vaccine During COVID—and Why It Matters

In late 2021, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) quietly changed its long-standing definition of a “vaccine.” While at first glance the change might appear semantic, critics argue it has broad implications for public trust, medical transparency, and even what qualifies as a vaccine under federal guidance.

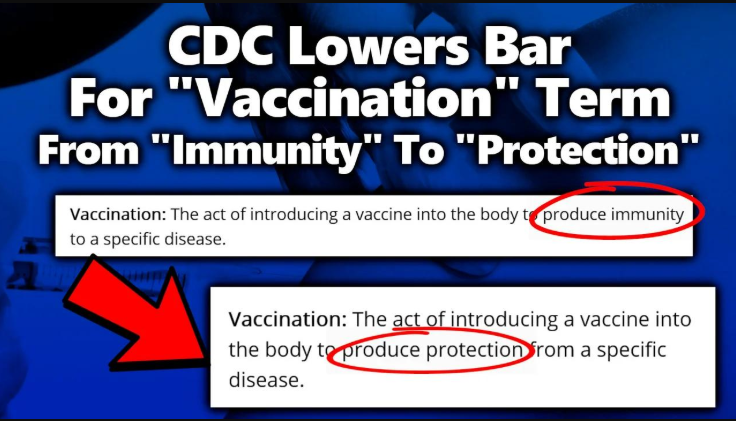

Until August 2021, the CDC defined a “vaccine” on its website as:

“A product that stimulates a person’s immune system to produce immunity to a specific disease, protecting the person from that disease.”

“Vaccination” was similarly defined as:

“The act of introducing a vaccine into the body to produce immunity to a specific disease.”

The term “immunity” was key here—it signified a clear, binary idea that one would be protected from contracting the disease in question after vaccination.

By September 2021, those definitions were changed. The new definition of a vaccine became:

“A preparation that is used to stimulate the body’s immune response against diseases.”

And vaccination:

“The act of introducing a vaccine into the body to produce protection from a specific disease.”

The term “immunity” was conspicuously removed, replaced by the more ambiguous phrase “protection,” and the language broadened significantly.

Officially, CDC spokespersons claimed the definition was updated for clarity and to better reflect the technology used in newer vaccines such as the mRNA-based COVID-19 shots from Pfizer and Moderna. But this explanation raised further questions.

According to internal emails released under FOIA requests, CDC staff were aware that the COVID-19 vaccines were not always preventing transmission or infection, especially as new variants like Delta emerged. The prior definition—which required a vaccine to “produce immunity”—was becoming a source of criticism and confusion. In one email from August 2021, a CDC official noted that the old definition was being “used by some to claim that COVID-19 vaccines are not vaccines.”

In effect, rather than publicly confronting these emerging limitations of vaccine performance, the CDC adjusted the language to make the products fit the label—rather than the other way around.

Under the revised language—"a preparation that is used to stimulate the body’s immune response"—the line between traditional vaccines and other immune-supporting interventions begins to blur.

The language is now ambiguous enough that a powerful pharmaceutical company might find ways to reclassify immune-supportive treatments as "vaccines" for regulatory or marketing advantage, especially under a loosely interpreted standard.

Legal and Regulatory Ramifications

Redefining “vaccine” impacts liability shields under laws like the PREP Act, and emergency use authorizations. If products qualify as vaccines, manufacturers can benefit from legal immunities—even when their products don’t provide immunity in the traditional sense.

Public Trust and Transparency

Changing definitions midstream—especially without clear public discourse—erodes trust. When citizens see government institutions moving goalposts, they’re less likely to believe future claims.

Philosophical Shift in Medical Language

Medicine has always relied on clear definitions for safety and clarity. This change represents a shift from objective outcomes (immunity) to vague intentions (protection), which could lower scientific standards and blur the distinction between treatment and prevention.

The redefinition of a vaccine by the CDC during the COVID-19 pandemic was more than a technical correction—it marked a significant departure from traditional medical language. Was it driven by political optics, pharmaceutical lobbying?

What is clear, however, is that the boundaries of what counts as a “vaccine” have been loosened—perhaps permanently.

It seems that COVID-19 Vaccines could not fit within the existing definition of a vaccine, we suggest this is the reason the changes were made.